Displaced people are more likely to have mental health problems

As written by Preeti Dhillon, exposure to traumatic events, food insecurity, and the length of displacement lead to a higher likelihood of mental health issues among IDPs. Previous studies in Nigeria, Ethiopia, Georgia and Kenya all indicate that IDPs are more likely than the non-displaced population to have mental health conditions. In Ukraine, 25 per cent of IDPs suffered from depression compared to 14 per cent of the general population. The estimated prevalence of depression among the global population is 3.4 per cent, nearly nine times less than the estimate for displaced populations.

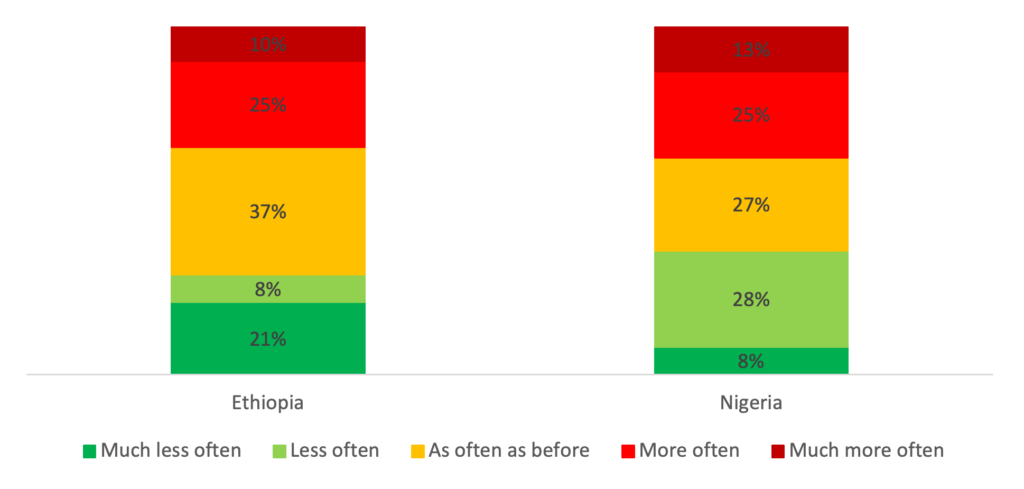

Research conducted by IDMC in Somalia, Ethiopia and Nigeria in 2021, published later this month, asked participants about their mental health before and after displacement. In Ethiopia and Nigeria, just over a third of respondents reported feeling worried, nervous, angry or sad more often than before they became displaced. People with a disability were twice as likely as IDPs without a disability to report that their mental health has worsened a lot since displacement.

Displacement also impacts the mental health of children and youth

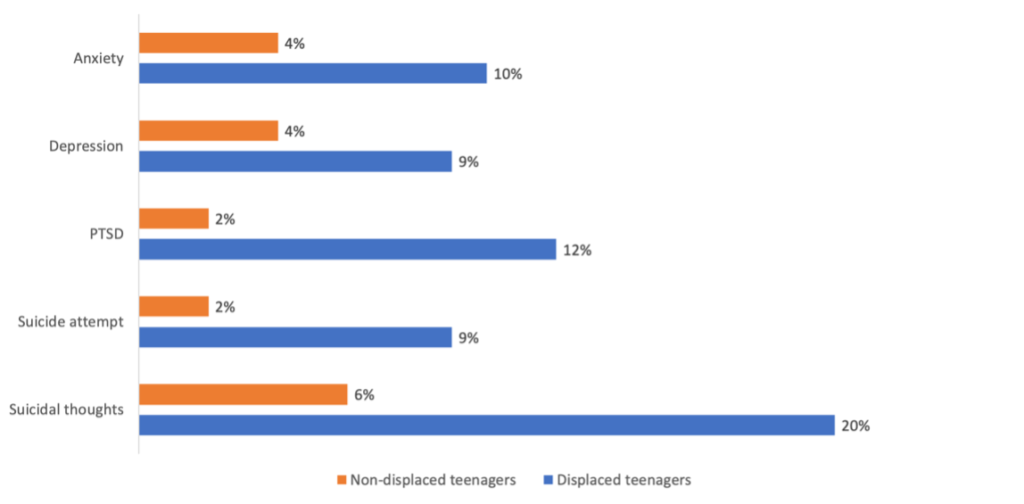

Reflecting the impact of displacement on mental health, displaced children and youth experience worse mental health than non-displaced populations. A study in Colombia found that anxiety and depression among displaced teenagers were more than twice as common as among non-displaced teenagers. Displaced teenagers were four and a half times as likely to have attempted suicide and six times as likely to have PTSD.

In Kachin state in Myanmar, mental health issues caused by displacement have been shown to have physical impacts on young people. An interviewee in one study noted that young girls “suffer stomach aches, psychological problems, and other diseases because of loss of appetite and not being able to concentrate”, at times prompting them to drop out of school.

Covid-19 has worsened IDPs’ mental health

Covid-19 has caused the mental health of people worldwide to deteriorate. For IDPs, the pandemic has compounded existing challenges such as restrictions on movement and limited access to livelihoods. Discrimination and stigma against IDPs, which causes mental health issues and exacerbates pre-existing conditions, has also increased as a result of Covid-19: in Nigeria, IDP settlements and camps were attacked due to rumours linked to the spread of Covid-19.

Mental health support is useful, but not always accessible

Before the pandemic, Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) was becoming commonplace in humanitarian settings. This has been shown to have a positive effect: an interpersonal therapy intervention with displaced children in Uganda led to a reduction in symptoms of depression. However, barriers that prevent the general population from accessing mental health care, such as stigma or a lack of mental healthcare specialists, also impact IDPs. In Pakistan, Bannu, whose population surged to two million as a result of conflict displacement, has only one psychiatrist. Access to mental health support has reduced further as a result of Covid-19 in the face of lockdowns and overwhelmed healthcare systems.

The examples given above illustrate a worrying trend. However, research on the relationship between mental health and displacement, and the effectiveness of different interventions, is still scarce. Further research is a pressing need. Understanding the scale of the problem and reducing barriers to mental health support are important steps towards improving the wellbeing of displaced populations.

originally from https://www.internal-displacement.org/